Can You Ever Forgive Me?: Jude Skewers the Status Quo

Ownership is an unsaid key word in Kontinental ’25, the latest perambulating spasm from Romanian director Radu Jude, which navigates an intersection of self-accountability, property, language, and culture as precarious notions in a nation bulldozing itself into capitalism’s future. A more omnipresent notion is guilt, mainly regarding its main protagonist, an empathetic bailiff who finds her world turned upside down when a homeless man she was in the process of evicting commits suicide. What follows is an endless parade of guilt performance as a way to reach absolution, perhaps more so in a public realm than the personal. However, these realities are perhaps more inextricable than the kindly heroine actually realizes.

Ownership is an unsaid key word in Kontinental ’25, the latest perambulating spasm from Romanian director Radu Jude, which navigates an intersection of self-accountability, property, language, and culture as precarious notions in a nation bulldozing itself into capitalism’s future. A more omnipresent notion is guilt, mainly regarding its main protagonist, an empathetic bailiff who finds her world turned upside down when a homeless man she was in the process of evicting commits suicide. What follows is an endless parade of guilt performance as a way to reach absolution, perhaps more so in a public realm than the personal. However, these realities are perhaps more inextricable than the kindly heroine actually realizes.

Orsolya (Eszter Tompa) is a woman who goes above and beyond in her profession as a bailiff in Cluj, the capital of Transylvania. Technically, she’s part of an ethnic minority as a Hungarian woman in the region, which works against her when a man she was trying to evict from squatting in the basement of a building sold to major real estate developers kills himself on the premises. Suddenly, she finds herself in an emotional tailspin. Despite having done everything she could to delay the eviction and relocate the man to a shelter, Orsolya feels she should have done more. But no one seems to agree with her.

Not unlike Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn (2021) or Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World (2023), a frazzled woman scurries about an increasingly hostile landscape of modern day Romania. Jude sets his sights on Cluj, Transylvania which became part of the Kingdom of Romania just over a century ago and arguably has a myriad of identity crisis issues lurking under its less homogenized surface. As Orsolya, Eszter Tompa (The Duke of Burgundy, 2014) ends up being one of Jude’s less sympathetic main players if mostly because the sheer level of repetition in her tour toward forgiveness ends up feeling exhaustingly performative. Guilt certainly becomes her, and the narrative, which consists mainly of a handful of one-on-one interactions, yields often funny, sometimes surprising results.

Initially, it seems she’s more preoccupied by her public image in the media fallout surrounding the suicide, which has found her characterized as an outsider, a callous Hungarian whose cruelties were responsible for the tragic death of an ex-athlete. She foregoes a planned family holiday to Greece because she’s so bothered by the situation, even going so far as tell her husband she’d considered suicide herself. An investigating police officer clears her immediately, comparing her to Oskar Schindler. “You can’t save everybody.”

Each conversation yields somewhat different viewpoints from various sources. Her sympathetic best friend tells her a story about a homeless man by her own home she’s seriously conflicted about, hating the smell of feces (which yields a surprising nod to Wim Wenders’ Perfect Days, 2023) but feeling guilty about how he has to live outside during the winter. Ultimately, she wishes her unhoused neighbor was dead. More strenuous is a knock-out sequence with her mother (Annamarie Biluska), who defends the fascist prime minister of Hungary and kicks Orsolya out of her home. She also has a rendezvous with an old student, who now works as a delivery boy. A night of drunken revelry and sex seems to alleviate her, briefly, but next she runs into the arms of an understanding priest who absolves her of not attending church lately. “It’s been under construction.”

Jude injects various cinematic references suggesting his social-surrealist aim utilizing Neo-realist parameters. Prior to the eviction, the gendarmerie reference the silent 1962 film A Bomb Was Stolen, directed by Ion Popescu-Gopo, a sci-fi comedy about the struggle over a nuclear bomb (notably, they fear the impending evictee is outfitted with his own explosive device—-and arguably, he kind of is). Jude injects outlandish elements into some visual sidelines, such as an ersatz amusement park made up of roaring animatronic dinosaurs in the forest and advanced technological toys shaped like pets (which notably seem to be allowed more ‘space’ than the unfortunate man who takes his own life).

The title is also referencing Roberto Rossellini’s 1951 classic Europa ’51, in which Ingrid Bergman plays a woman driven to bettering herself after her child commits suicide (the poster of this is featured prominently in one sequence, as well). Orsolya never really gets anyone to confront her with the obvious, that she, along with everyone else, could really do a lot more to make the world a better place and alleviate suffering. Instead, every time she relays the story, the phrase about how she’s “legally” okay always comes up, prompting relief. At the end of the day (and the end of the film), transforming landscapes and replenishing real estates will eclipse all the collateral damage such gentrification entails. What else can she do except wring her hands?

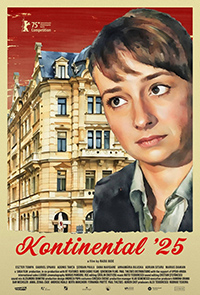

Reviewed on February 19th at the 2025 Berlin International Film Festival (75th edition) – Main Competition. 109 mins.

★★★½/☆☆☆☆☆